Inflation can be considered an invisible 'tax' that leads to a loss of purchasing power, i.e. inflation is an upward movement in the average level of prices. Warren Buffett calls inflation a far more devastating 'tax' than anything that has been enacted by legislation. For a very simplistic understanding of inflation let's consider the following example. Imagine that:

- you have savings of R100 today which you don't invest in a secure but high yielding investment (the kind of investments we make at Richland IH)

- a can of Coca-Cola costs R10 today

- the average annual inflation rate in the country is 100% (the actual South African inflation rate is close to 6% per annum, but we will use 100% for the sake of the example)

- as a result of inflation that same can of Coca-Cola will cost R20 (i.e. R10 * 100% + R10 = R20)

- therefore, if you can currently buy 10 cans of Coca-Cola with your R100 (i.e. R100 / R10 = 10) you will be able to buy only 5 cans of Coca-Cola with your R100 in a years time due to inflation (i.e. R100 / R20 = 5)

Governments would like inflation to be under control, i.e. not too high and not too low. Both these situations are bad for economic growth and poor economic conditions (or growth) which leads to instability, tough times for a country's citizens, and it makes it hard for a political party to remain in power. Governments mainly use one of two methods to control inflation: either fiscal policy (related to government spending and taxes) or monetary policy (the supply of money in the economy). Governments rely heavily on monetary policy to control inflation. Monetary policy is the process by which the monetary authority of a country (i.e. the government) controls the supply of money, often targeting a rate of interest for the purpose of promoting economic growth and stability. To stimulate a country's economy the monetary authority will lower interest rates in the hope that easy credit will entice businesses into expanding. Conversely, increasing interest rates is intended to slow inflation in hopes of avoiding distortions and deterioration of asset values.

This brings me to the crux of the discussion, i.e. rising and lowering inflation rates and the value investor. The bottom line is that rising and lowering inflation rates has a direct effect on bond yields and stock prices. Understanding this sacrosanct, correlative relationship is important to the value investor and should never be ignored. In short, rising inflation rates cause bond yields to rise and P/E ratios of shares to decline. Therefore, over longer periods stock and bond prices tend to react similarly to the same economic information. The next section will explain this relationship using examples with bonds, coupons, dividends, etc. to show the reaction of bonds and stocks to inflation.

Before I start explaining the relationship between inflation and bonds, I need to specify some information regarding bonds (for those that don't know anything about bonds). Each bond has an expected return and as investors we are interested in understanding how much it is. Yield is the measure used most frequently to estimate or determine a bond's expected return. Yield is also used as a relative value measure between bonds. There are two primary yield measures that must be understood to understand how different bond market pricing conventions work: yield to maturity and current yield.

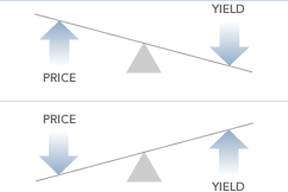

A yield-to-maturity calculation is made by determining the interest rate (discount rate) that will make the sum of a bond's cash flows, plus accrued interest, equal to the current price of the bond. Current yield is the anticipated return on an investment, expressed as an annual percentage. It is the coupon value / price of the bond. Whichever way you calculate yield, the relationship between price and yield remains constant: The higher the price you pay for a bond, the lower the yield, and vice versa. Here, we will use yield as the yield-to-maturity when referring to a bond yield. To illustrate yield-to-maturity I have created a little example.

Imagine a bond with a face value of R1000 currently selling for R950 in the market. It pays a coupon of 8.5% per year (roughly the same as the current South African Risk Free Rate of return - a return determined primarily by the inflation rate and expected economic growth rate of South Africa), which we assume to be the current prime interest rate in South Africa. The 8.5% coupon rate will ensure an annual coupon of R85. In my example the bond will mature in two years, i.e. return the principal of R1000 to the holder of the bond.

| Face Value | R 1,000.00 | |

| Current Price | R 950.00 | |

| Coupon Rate | 8.50% | |

| Discount Rate | 11.40% | |

| Year | 1 | 2 |

| Coupon Values | R 85.00 | R 85.00 |

| Principal Value | R 1,000.00 | |

| Total Return | R 85.00 | R 1,085.00 |

| Discount Factor | 0.90 | 0.81 |

| Discounted Value | R 76.30 | R 874.30 |

| Total Value | R 950.60 |

The question is what happens when the interest rate of 8.5% goes to 10%? Let's imagine the bond above was issued two months ago at R1000 par value and now (two months hence) the interest rate changed to 10%. Bonds currently being issued will pay a coupon rate of 10%, instead of the 8.5% of two months ago, and thus have a yield to maturity of 10%. This implies that someone buying and holding this bond will pay R1000, and receive two coupon payments of R100 each as well as the original R1000 in two years. And what happens to the bonds issued two months ago at 8.5%? Their prices have to be revalued down in order to make them more or equally as attractive as the current bonds! To understand this, look at the DCF below and consider that we now have to discount the coupons and principal at 10% (the current interest rate) instead of 8.5%. Using 10% (my new yield-to-maturity) instead of 8.5% (coupon rate at time of issue) results in a higher discount factor and therefore reduces the current value of the bond. In summary, you can consider it like this: if current bonds give a better return that existing bonds then existing bonds are less attractive and have to sell at a discount

From this explanation it is clear that in the first example above, with the par value (R1000) > current bond price (R950), that the interest rate was less than 8.5% at the time the bond was issued. Therefore, the value of the bond decreased to R973.97 and the yield of the bond increased to 10% when interest rates increased.

Interest Rate at 10%

| Face Value | R 1,000.00 | |

| Current Price | R 973.97 | |

| Coupon Rate | 8.50% | |

| Discount Rate | 10.00% | |

| Year | 1 | 2 |

| Coupon Values | R 85.00 | R 85.00 |

| Principal Value | R 1,000.00 | |

| Total Return | R 85.00 | R 1,085.00 |

| Discount Factor | 0.91 | 0.83 |

| Discounted Value | R 77.27 | R 896.69 |

| Total Value | R 973.97 |

Interest Rate at 7.00%

| Face Value | R 1,000.00 | |

| Current Price | R 1,027.12 | |

| Coupon Rate | 8.50% | |

| Discount Rate | 7.00% | |

| Year | 1 | 2 |

| Coupon Values | R 85.00 | R 85.00 |

| Principal Value | R 1,000.00 | |

| Total Return | R 85.00 | R 1,085.00 |

| Discount Factor | 0.93 | 0.87 |

| Discounted Value | R 79.44 | R 947.68 |

| Total Value | R 1,027.12 |

| Inflation | Interest Rates | Bond Prices | Bond Yields |

| Rise | Rise | Lower | Rise |

| Lower | Lower | Rise | Lower |

I start by remind you that shares have a yield as well, it's the annual earnings per share divided by the price per share (or E/P). You will be familiar with P/E (or the Price-to-Earnings) ratio that I often write about here. Therefore, a shares yield is the inverse of it's P/E ratio. Let's consider this for a minute. When a share has a P/E ratio of 10 it has an earnings yield of 1 / 10 = 10%. A P/E ratio of 15 is an earnings yield of 1 / 15 = 6.7% and finally a P/E of 5 is an earnings yield of 20%. Therefore, as value investors we are interested in shares with low P/E ratio's which have high earnings yield.

We don't often think of shares as bonds, but they are actually, albeit bonds with 'less than guaranteed' coupons. The shares we buy all have annual earnings per share, or essentially an annual 'coupon'. Whatever profits the company generates each year are legally owed to its shareholders. This is where the relation between shares and bonds lie. The major difference is that a bond's coupon and face value are (almost) guaranteed by the issuer and therefore reduces the risk of the investor (the major risk remaining is credit/default risk of the issuer of the bond). In the case of a share there are no such guarantees.

In most cases a company retains all or part of its profits and reinvests them to generate, I hope, higher earnings in future (thereby compounding your investment). Therefore, just like a bond investor, our goal should be to choose investments whose yearly returns, or coupons, are stable, secure, more than compensate for inflation, and beats bond yields (to compensate for holding an instrument whose coupon is not assured)!

Let's take this thinking back to our example. We assumed that our current Risk Free Rate was 8.5% and therefore a firm earning R1.00 profit per share needs to trade (i.e. have a price of) for R11.76 (R1.00 / 8.5% = R11.76) to yield the same 8.5% (P/E = R11.76 / R1.00 = 11.76 and therefore has an earnings yield of 1 / 11.76 = 8.5%). Next we assume (correctly I believe) that the firm possesses more risk than a bond and therefore the shares of the firm will be priced at lower than R11.76 per share, which in turn leads to a higher earnings yield. At a price of R10, the R1.00 earnings would represent a 10% yield. Due to the fact that investors always have a choice between investing in bonds or shares (or other investment classes), share prices and yields will (in general) follow bond yields. This then brings me to the conclusion of my post and illustrated in the table below:

| Inflation | Interest Rates | Bond Prices | Bond Yields | Share Prices | Earnings Yield |

| Rise | Rise | Lower | Rise | Lower | Rise |

| Lower | Lower | Rise | Lower | Rise | Lower |

- when inflation and interest rates rise both bond and share prices fall (and their yields rise)

- when inflation and interest rates fall both bond and share prices rise (and their yields fall)

With the above knowledge in mind you could be asking: why buy shares, considering the additional risk, rather than bonds? The answer is simple: if you select the right shares they will have the ability to outperform bonds over the long term. Warren Buffett says a share should be thought of as a bond substitute, a dynamic security that has the capability of providing you will less or more income each year than it did the preceding year. However, when picking a share to invest in make sure that you find a firm:

- whose returns beat inflation

- whose returns beat the risk free rate

- whose current earnings yield (i.e. inverse of its P/E ratio) is near or above yields on long-term bonds

- which might currently have an earnings yield lower than long-term bond yields, but is growing and is expected to generate an earnings yield that would soon surpass bond yields

- that you can buy at the cheapest possible price because that's the best way of ensuring that you can beat bond yields by a wide margin

I hope you have enjoyed this post. Contact me if you have any additional questions regarding this subject.

Be extraordinary!

Myles Rennie

RSS Feed

RSS Feed