Valuation Basics - The Financial Statements 2

In this post I continue to look at the balance sheet, but now I will consider liabilities and equity.

Balance Sheet

In the previous post I discussed elements pertaining to the assets on the balance sheet. In this post I will focus on liabilities and equity.

Liabilities

Liabilities are also classified into current and non-current liabilities. Similar to assets, current liabilities are defined as anything that will have to be settled (paid) within 12 months. All other liabilities are non-current liabilities.

Equity

In the previous post I discussed elements pertaining to the assets on the balance sheet. In this post I will focus on liabilities and equity.

Liabilities

Liabilities are also classified into current and non-current liabilities. Similar to assets, current liabilities are defined as anything that will have to be settled (paid) within 12 months. All other liabilities are non-current liabilities.

Equity

Typical Liability Adjustments

As mentioned in The Financial Statements 1 performing either book value, replacement value, or liquidation value revaluations requires adjustments to the entire balance sheet (assets and liabilities) in order to reflect the economic value of the balance sheet. Being a value investor makes me a conservative investor. Therefore, I don't like to fiddle with liabilities much and take a very conservative approach to making any adjustments. Below is a short list of (typical) liability adjustments:

As mentioned in The Financial Statements 1 performing either book value, replacement value, or liquidation value revaluations requires adjustments to the entire balance sheet (assets and liabilities) in order to reflect the economic value of the balance sheet. Being a value investor makes me a conservative investor. Therefore, I don't like to fiddle with liabilities much and take a very conservative approach to making any adjustments. Below is a short list of (typical) liability adjustments:

- I accept any prepaid expenses at book value

- Leases

- Options

Net Asset Value or Book Value

Finally, we get to the valuation discussion. I have been working toward this point to allow the user to perform an asset valuation. With an adjusted balance sheet the process of determining the Net Asset Value (NAV) or Book Value (BV) is simple. You subtract the adjusted Liabilities from the adjusted Assets, which leaves you with the NAV. If you take this value and divide it by the diluted number of shares you have the NAV or (better known) BV per share.

BV can be used for many different purposes. For instance, from here you can calculate the Price-to-Book ratio by dividing the current market price per share by the book value per share. This is an important ratio for value investors as we like to focus on companies with low price-to-book values. Price-to-book is so important that Benjamin Graham used it in the following manner:

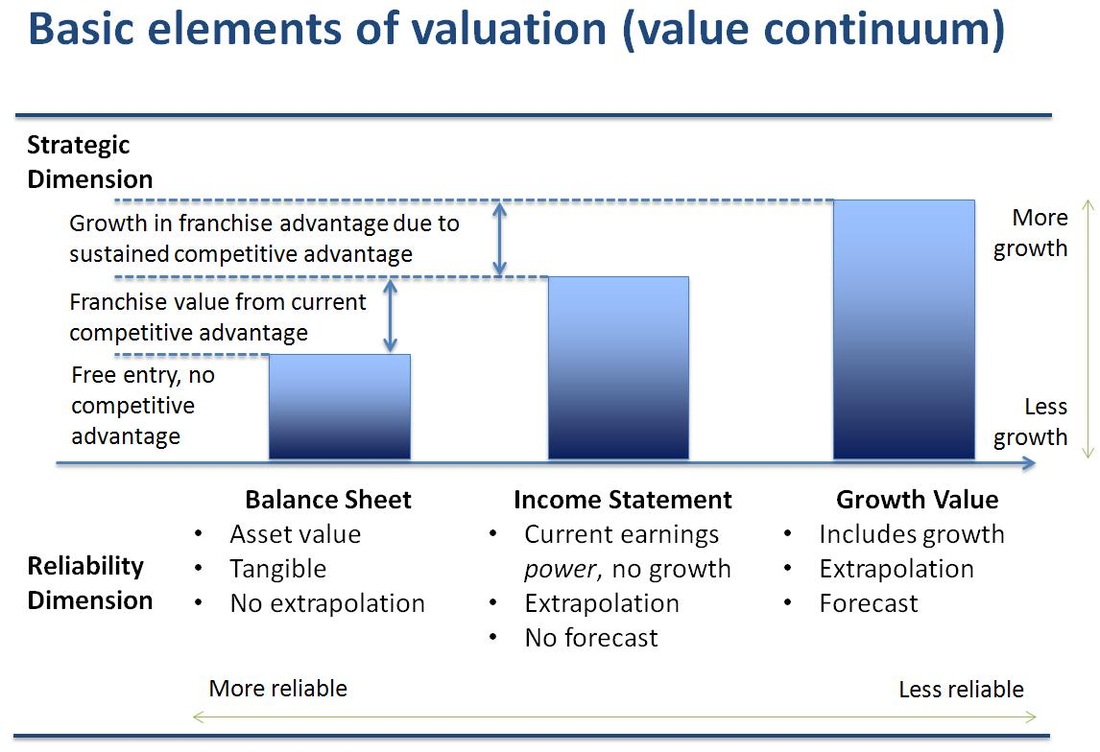

Book value seems to become very important overnight when times are hard (I wonder why...!?). I use book value per share as an indication of intrinsic value per share (see value continuum to understand where book value fits in) when considering whether to buy a share at a given market price. Therefore, I like quality companies trading at low price-to-book values, e.g. an established company with a durable competitive advantage, good management and a price-to-book ratio of close to 1 is fantastic! I consider anything near 1 and up to 1.5 or 1.6 very acceptable.

I should however also warn against the weaknesses of book value. For industrial companies with fixed assets book value provides good insights. For companies in the service industry (e.g. consulting firms) business book value could be misleading. Due to relatively small asset base they will typically trade at higher price-to-book values. Value investors who has a circle of competence in this area, and invest in it, will have to adjust their screening criteria to consider these higher ratios. Also, companies growing fast will have higher than average price-to-book ratios and again the value investor focusing on companies in this phase of their business life-cycle will adjust their valuation criteria to consider this.

Finally, we get to the valuation discussion. I have been working toward this point to allow the user to perform an asset valuation. With an adjusted balance sheet the process of determining the Net Asset Value (NAV) or Book Value (BV) is simple. You subtract the adjusted Liabilities from the adjusted Assets, which leaves you with the NAV. If you take this value and divide it by the diluted number of shares you have the NAV or (better known) BV per share.

BV can be used for many different purposes. For instance, from here you can calculate the Price-to-Book ratio by dividing the current market price per share by the book value per share. This is an important ratio for value investors as we like to focus on companies with low price-to-book values. Price-to-book is so important that Benjamin Graham used it in the following manner:

- Price-to-book ratio sets the floor for a stock price (if price-to-book was calculated using liquidation assumptions then under worst case scenario this ratio indicates how much of your investment you will recover)

- Higher price-to-book ratio's indicate greater risk during liquidation (i.e. the less likely there will be enough assets to pay all the debts and have money left for shareholders)

- If price-to-book ratio's move or become much higher than reasonable (or normal) for a particular stock or industry it could be a signal to sell (if an alternative investment, promising better returns, is available or if something fundamental in the business has shifted and requires exit)

- Inspect and screen out companies that don't have stable and growing yearly book values per share. Book value per share, as Buffett says, is the proxy he uses for determining intrinsic value per share. He considers it so important that he measures himself and Charlie Mungers' performance at Berkshire Hathaway in terms of yearly increasing book value per share (as reported in Berkshire's annual report - usually on page 2 of the annual report!)

- He screened out any stock which had a Price-to-book ratio, multiplied by Price-to-EPS ratio, of more than 22. Graham called it his Price-to-book test.

Book value seems to become very important overnight when times are hard (I wonder why...!?). I use book value per share as an indication of intrinsic value per share (see value continuum to understand where book value fits in) when considering whether to buy a share at a given market price. Therefore, I like quality companies trading at low price-to-book values, e.g. an established company with a durable competitive advantage, good management and a price-to-book ratio of close to 1 is fantastic! I consider anything near 1 and up to 1.5 or 1.6 very acceptable.

I should however also warn against the weaknesses of book value. For industrial companies with fixed assets book value provides good insights. For companies in the service industry (e.g. consulting firms) business book value could be misleading. Due to relatively small asset base they will typically trade at higher price-to-book values. Value investors who has a circle of competence in this area, and invest in it, will have to adjust their screening criteria to consider these higher ratios. Also, companies growing fast will have higher than average price-to-book ratios and again the value investor focusing on companies in this phase of their business life-cycle will adjust their valuation criteria to consider this.

Next Steps (...next posts)

Next I will look at the Income Statement and Earnings Power Value. Once this is done I will review the growth assets and the two Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) valuations starting from respectively Free Cash Flow to Firm and Free Cash Flow to Equity holders. Once done we will have all three intrinsic value estimates for a firm, i.e. the asset value, earnings power value and growth values.

Please send me your comments or questions. I look forward to hearing from you.

Be Extraordinary!

Myles Rennie

Next I will look at the Income Statement and Earnings Power Value. Once this is done I will review the growth assets and the two Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) valuations starting from respectively Free Cash Flow to Firm and Free Cash Flow to Equity holders. Once done we will have all three intrinsic value estimates for a firm, i.e. the asset value, earnings power value and growth values.

Please send me your comments or questions. I look forward to hearing from you.

Be Extraordinary!

Myles Rennie

RSS Feed

RSS Feed