Valuation Basics - The Financial Statements 1 Before I start my next valuation (it will be done on Assore Limited) I want to spend some time focusing on why and how value investors look at both the Balance Sheet and Income Statement of a company when performing a detailed analysis of a company. OverviewMany people don't like spending time reviewing financial statements. There are many reasons for this, e.g. they might not understand it, it might be too much work, they could be following an investment strategy that does not require study of any financial statements. Unfortunately (or in my case fortunately) the true value investor has to spend time studying these black-and-white pages containing the information required to make good investment decisions. For a value investor the intrinsic value of an investment lies hidden in the financial statements. By gaining a rudimentary understanding of these (easier than expected) documents investors will find that they are not as scary as they first seem. When studying financial statements there are my point to consider. The value investor should consider that: - The balance sheet tells about the firms Assets, Debt and Equity. Assets, the core of most businesses (at least most value investment businesses), can tell about stability, safety, growth potential, and the quality of management. Debt can help firms grow, but increases the riskiness of a business during economic distress. Debt places a burden on earnings and too much of it has lead to the downfall of many businesses.

- The income statement tells about a firms revenue, quality of earnings, sales vs. operational efficiency, has the ability to highlight potential, earnings, and the quality of management.

I will here again repeat Benjamin Graham's definition of an investment: "it is an operation which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and an adequate return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative." Safety, in Graham's opinion, is measured in terms of stability based on known information. When valuing stocks (i.e. determining intrinsic value) Graham focused on current information contained in financial statements, and not as much on predicting the future. In a speech in 1975 he is quoted as saying: "I have resolutely turned my back on efforts to predict the future." Intrinsic value is an elusive concept. Ask 10 people to value an asset and you will receive 10 different answers. Value investors have been debating for many years whether to focus on the quality of assets and the balance sheet or whether to focus on the quality of earnings and the income statement to determine intrinsic value. Even the best known value investor of all time, Warren Buffett, has changed his opinion on this matter over the years. In the past he often emphasized the importance of the income statement (for quality earnings and growth) and in recent years he has shifted partially back to assets that can sustain and help a firm in times of recession, inflation, etc. Irving Khan, Graham's teaching assistant at Colombia University, said: "We stress balance sheet and assets. We're old fashioned because our paramount aim is preservation of capital." Walter Schloss, another of Graham's disciples who recently passed away, also emphasized the importance of the balance sheet. These investors all obtained impressive compound annual returns over many years. I prefer a balanced valuation view to include the following three elements: - Existing assets derived from the balance sheet

- Earnings power derived from the income statement

- Growth assets, and related earnings potential, derived from growth assets (determined by reinvestment rates, etc.) on the balance sheet

If a company can present a compelling investment opportunity based on all three investment approaches, then I feel comfortable to consider investing, but only if I can buy at the right price and after passing my Phase I criteria. Balance SheetI like Janet Lowe's analogy of the income statement and balance sheet in her book The Triumph of Value Investing. She says that if a firm was a ship the balance sheet would be the hull and the income statement would be the sails. The hull keeps the business afloat while the sails - propelled by sales - moves it forward. With this analogy in mind, let's start considering what details of a business' hull do we need to check in order to determine whether it will remain afloat. The balance sheet works according to a simple core relationship, and it is: Assets = Liabilities + Shareholder Equity Balance sheets work based on accrual accounting, meaning that revenue and expenses are recognized in the periods in which they are incurred, irrespective of whether cash was involved. It is therefore a statement of financial position, a snapshot of the assets and liabilities at a single point in time. When I start looking at the balance sheet, I focus on five key aspects: - Existing assets

- Growth assets

- Cash, marketable securities and investments

- Debt

- Equity, dividends and retained earnings

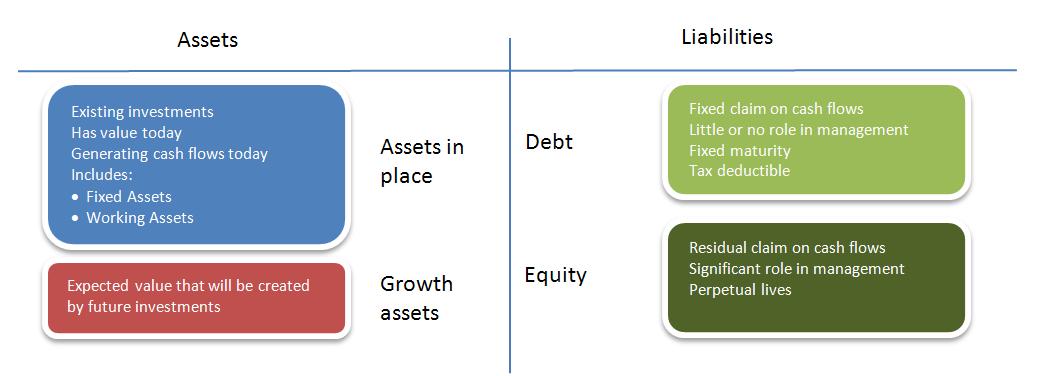

AssetsLet's first consider the difference between existing assets vs. growth assets. Aswath Damodaran, in his book Demodaran on Valuation: Security Analysis for Investment and Corporate Finance, argues that the value of a business could be considered the sum of the values of the individual assets owned by the business, as opposed to the discounted value of all expected future cash flows generated by the assets the business owns. He favours valuing businesses as going concerns, i.e. discounting the conservative future free cash cash flow of the business (generated by assets it already owns and assets it expects to invest in in future) by a risk-adjusted discount factor. To better understand these two 'classes' of assets he proposes visualizing the balance sheet in the form of a 'financial balance sheet' (as opposed to an accounting balance sheet) with investments already made as 'assets in place' and investments we expect to make in the future are 'growth assets'. | | When I do a asset-based valuation, i.e. to determine either book value or replacement asset value, I am focusing only on the existing assets in place and ignore growth assets completely.

| Growth assets only play a role in my growth valuation, performed as the last of three valuation techniques to determine the intrinsic value of a firm (see the image in the section The Value Continuum below). It is clear the picture above that pure asset-based valuations will yield lower values than going concern (or growth) valuations. A couple of brief ideas on assets. Assets are classified as either current or non-current and then there is the distinction between tangible and intangible assets. Current assets are defined as anything that will be turned into cash within 12 months under normal operating conditions. These include cash, cash equivalents, short-term investments, accounts receivable, inventory, and different types of prepaid accounts (e.g. tax). All other assets are non-current assets. Assets can alternatively be classified as tangible or intangible. Tangible assets are sometimes called hard assets and include things like inventory, property, plant, equipment, and cash. All other assets are classified as intangible. CashCash gives a company the ability to weather hard times or take opportunities. On the other hand cash does not earn good returns. Stable cash positions indicates the existence of a durable competitive advantage (in cases where debt levels are consistently low - else debt can be used to smooth cash positions) and eludes to quality, conservative management. Too little cash can constrain the business and stop it from growing or staying afloat. In order to calculate growth assets intrinsic value I will return to cash and specifically the concept of Free Cash Flow, i.e. cash available to the firm or to equity holders after working capital and capital expenditure requirements have been considered. What I would like to say here is that stability in free cash flow, and more specifically positive average free cash flow, is important to the value investor. Free cash flow could be negative for many reasons and could: - signal good things in future, e.g. high growth companies investing more than it is earning

- signal danger, e.g. companies slowly dying and has negative earnings or consuming itself by divesting assets or shrinking capital

- signal possible good returns, e.g. companies that in the past over-invested (capital overspending) and could now benefit from it in the next couple of years

- signal that management might make new stock issues or raise debt (in the case of persistent, even short-term, negative FCFE)

Understanding cash positions, working cash, excess cash, free cash flow, and the application of cash in a company is very important...and a subject on its own. Liabilities and Equity to be discussed in a following post, i.e. Financial Statements 2Typical Asset AdjustmentsPerforming either book value, replacement value, or liquidation value revaluations requires adjustments to the entire balance sheet (assets and liabilities) in order to reflect the economic value of the balance sheet. Typical adjustments include revaluation (mark-to-market) of investments, considering non-operating assets, etc. Please note, and this is very important, that the adjustments made differ for book value calculations vs. replacement asset value calculations! Below is a short list of (typical) asset adjustments: - Marketable securities and short-term investments - determine present market value by marking to market

- Accounts receivable - adjust to net realizable value (book value) or economic value (replacement asset value), e.g. bad debt allowance must either be netted or added

- Inventory consist of raw material, work in progress, and finished goods. If it will be sold in 12 months it will be included in current assets else non-current assets. Adjustments to inventory can be tricky, for instance, if the inventory control system is LIFO and prices are rising then a LIFO reserve (often as high as 20%) has to be added to the inventory asset. To determine any other adjustments to inventory the analyst must determine whether inventory days have been increasing (i.e. inventory turning slower). If it has been increasing then inventory asset value has to be adjusted downward based on the following rules: more commodity type inventory should be adjusted down a little (e.g. down by 25% or 75% of the original value), unsalable inventory should be adjusted down more ( e.g. down by 50% or 50% of the original value), and specialized inventory should be adjusted down the most (e.g. down by 75% or 25% of the original value)

- In the case of replacement asset value prepaid accounts (like deferred taxes), to be 'turned into cash' or 'bartered' within the next 12 months, should be discounted to present value. Using a discount rate of 15% this yields a discount factor of (1/(1+15%)^1=86.95% (i.e. down by 13% or 87% of the original value). In the case of deferred tax assets, it should be offset against any deferred tax liability, and the remaining amount (either asset or liability) should be discounted to its present value (PV) by the appropriate discount rate

- Property, plant and equipment should be considered separately. In the case of a reproduction valuation the historical cost of the different categories of PPE (i.e. property, plant and equipment) have to be considered individually. Property could be estimated based on current market values (or rather fair market values). Plant and equipment could probably be reduced as a result of technical innovation constantly driving down prices (except if plant has recently been replaced)

- Goodwill, when referring to intangible assets used to create value for the firm such as product portfolio, special licenses, customer relationships, competitive advantage, intellectual property, and so on, will probably have to be adjusted upward in order to determine true asset value. However, be careful not to be too optimistic when calculating realistic asset replacement or economic value. It is often not possible to accurately calculate the value of these intangible assets, and here Prof. Bruce Greenwald suggest a shorthand, i.e. use a multiple of the selling, general, and administration (SGA) cost, in most cases between one and three years' worth

- Capitalization of R&D expenses. Often companies expense R&D costs on an annual basis. However, these are actually assets of the company and have to be treated as such. I realize that most value investors shy away from companies with substantial R&D divisions and will therefore never be faced with having to consider capitalizing R&D. For completeness sake, and for situations where needed, I will briefly explain the process here. To capitalize R&D assets we have to start by considering how long it takes, on average, for it to be converted into commercial products. We can take here, as example, five years, which I will consider to be the amortization duration for the asset. Next I have to collect the cost of the expense over the past years ranging back to the amortizable life of the R&D asset. If this cost was uniform then I can calculate the value of the asset as the proportionate sum of the expense over the last five (I chose five as an example) as 1/5 of the cost 5 years ago plus 2/5 of the cost 4 years ago plus 3/5 of the cost 3 years ago plus ... and this years entire R&D expense to arrive at the value of the R&D asset (these are the unamortized amounts of the asset left if assumed that the lifetime is 5 years and the amortization process is linear across the lifetime, which yields 20% per year over 5 years). The effect of book value of equity is therefore: adjusted book value of equity = book value of equity + value of R&D asset. There is however an additional element to consider, and this impacts the Income Statement. The operating income has to be adjusted to consider amortization of the asset instead of the R&D expense. Adjusted operating income = Operating income + R&D expense - Amortization of R&D asset.

- Other adjustments. There are other adjustments than can be made, e.g. financing subsidiaries (e.g. BMW financial services), non-consolidated subsidiaries, prepaid pension assets, etc. These assets must be approached with caution and any adjustments must be carefully considered. In case of doubt, be very conservative and either exclude from the balance sheet or show at low values. In cases where operating expenses (or one of expenses) are capitalized as assets (and subsequent adjustments) care is needed to consider whether the adjustment has a pre-tax or post-tax effect on the Income Statement. Capitalization of pre-tax expenses, like R&D expense, is entirely tax-deductible and therefore no more adjustments are needed. Some companies, like Coca-Cola, could consider capitalize advertising spend because one can argue that it contributed to their brand value. Other companies, like consulting houses, could consider capitalizing recruitment and training fees of their most valuable assets, i.e. people. Amazon could capitalize SGA costs arguing that these expense contribute to brand value and help bring in new long-term customers.

What we are trying to achieve with these adjustments is to be "approximately right rather than precisely wrong". I acknowledge that to value an asset with 100% accuracy is very unlikely, but it is possible to value it within an acceptable margin of safety. These adjustments can be tricky and would be happy to answer any questions about them. Feel free to contact me and I will gladly provide examples and explain them as well. Next Steps (...next posts)

Next I will look at some of the other Balance Sheet items (Liabilities and Equity) and then move on to the Income Statement (for the Earnings Power value) and then the growth assets (for the Discounted Cash Flow valuations).

Please send me your comments or questions. I look forward to hearing from you.

Be Extraordinary!

Myles Rennie

Valuation Basics - The Financial Statements 2 In this post I continue to look at the balance sheet, but now I will consider liabilities and equity. Balance Sheet

In the previous post I discussed elements pertaining to the assets on the balance sheet. In this post I will focus on liabilities and equity.

Liabilities

Liabilities are also classified into current and non-current liabilities. Similar to assets, current liabilities are defined as anything that will have to be settled (paid) within 12 months. All other liabilities are non-current liabilities.

Equity

Typical Liability AdjustmentsAs mentioned in The Financial Statements 1 performing either book value, replacement value, or liquidation value revaluations requires adjustments to the entire balance sheet (assets and liabilities) in order to reflect the economic value of the balance sheet. Being a value investor makes me a conservative investor. Therefore, I don't like to fiddle with liabilities much and take a very conservative approach to making any adjustments. Below is a short list of (typical) liability adjustments: - I accept any prepaid expenses at book value

- Leases

- Options

As mentioned before, I approach adjustment to try and ensure that I am "approximately right rather than precisely wrong". These adjustments can be tricky and would be happy to answer any questions about them. Feel free to contact me and I will gladly provide examples and explain them as well. Net Asset Value or Book ValueFinally, we get to the valuation discussion. I have been working toward this point to allow the user to perform an asset valuation. With an adjusted balance sheet the process of determining the Net Asset Value (NAV) or Book Value (BV) is simple. You subtract the adjusted Liabilities from the adjusted Assets, which leaves you with the NAV. If you take this value and divide it by the diluted number of shares you have the NAV or (better known) BV per share. BV can be used for many different purposes. For instance, from here you can calculate the Price-to-Book ratio by dividing the current market price per share by the book value per share. This is an important ratio for value investors as we like to focus on companies with low price-to-book values. Price-to-book is so important that Benjamin Graham used it in the following manner: - Price-to-book ratio sets the floor for a stock price (if price-to-book was calculated using liquidation assumptions then under worst case scenario this ratio indicates how much of your investment you will recover)

- Higher price-to-book ratio's indicate greater risk during liquidation (i.e. the less likely there will be enough assets to pay all the debts and have money left for shareholders)

- If price-to-book ratio's move or become much higher than reasonable (or normal) for a particular stock or industry it could be a signal to sell (if an alternative investment, promising better returns, is available or if something fundamental in the business has shifted and requires exit)

- Inspect and screen out companies that don't have stable and growing yearly book values per share. Book value per share, as Buffett says, is the proxy he uses for determining intrinsic value per share. He considers it so important that he measures himself and Charlie Mungers' performance at Berkshire Hathaway in terms of yearly increasing book value per share (as reported in Berkshire's annual report - usually on page 2 of the annual report!)

- He screened out any stock which had a Price-to-book ratio, multiplied by Price-to-EPS ratio, of more than 22. Graham called it his Price-to-book test.

My aim here was to calculate book value per share (of the existing assets and ignoring any growth assets), which we have finally achieved. I have also briefly touched on some important aspects of book value (i.e. using price-to-book value as an example). There is much more to be said on understanding various ratio's (especially when screening possible investments or when performing a relative valuation). In a follow-up series of posts I could stop to discuss these. Book value seems to become very important overnight when times are hard (I wonder why...!?). I use book value per share as an indication of intrinsic value per share (see value continuum to understand where book value fits in) when considering whether to buy a share at a given market price. Therefore, I like quality companies trading at low price-to-book values, e.g. an established company with a durable competitive advantage, good management and a price-to-book ratio of close to 1 is fantastic! I consider anything near 1 and up to 1.5 or 1.6 very acceptable. I should however also warn against the weaknesses of book value. For industrial companies with fixed assets book value provides good insights. For companies in the service industry (e.g. consulting firms) business book value could be misleading. Due to relatively small asset base they will typically trade at higher price-to-book values. Value investors who has a circle of competence in this area, and invest in it, will have to adjust their screening criteria to consider these higher ratios. Also, companies growing fast will have higher than average price-to-book ratios and again the value investor focusing on companies in this phase of their business life-cycle will adjust their valuation criteria to consider this. Next Steps (...next posts)

Next I will look at the Income Statement and Earnings Power Value. Once this is done I will review the growth assets and the two Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) valuations starting from respectively Free Cash Flow to Firm and Free Cash Flow to Equity holders. Once done we will have all three intrinsic value estimates for a firm, i.e. the asset value, earnings power value and growth values.

Please send me your comments or questions. I look forward to hearing from you.

Be Extraordinary!

Myles Rennie

Valuation Basics - The Financial Statements 3 In this post we will examine the Income Statement and Earnings Power Value.

Valuation Basics - The Financial Statements 4 In this post we will consider how the information in the Balance Sheet and Income Statement is used to perform a Discounted Cash Flow analysis.

Valuation Basics - Putting the Financial Statements together This post puts together the previous discussing valuations and the financial statements. Therefore, to understand where are how this post first in you should read the proceeding posts please. The Valuation Process

To start off I will talk about the truth of valuation. Firstly, all valuations are biased. No one starts with a blank sheet and we all approach valuation with our own views before even starting, e.g. it starts with the companies we choose to value. With professional analysts there are institutional factors that create bias, e.g. herding, window dressing, etc. The inputs to your valuations reflect your optimistic or pessimistic position, e.g. loss aversion, lotteries, etc. Then there is the post valuation garnishing's

Most valuations (even good ones) are wrong. We expect to get the right answer when we follow the right steps. While this is true in baking and science, it is not the case in valuation. Even if your data sources are impeccable, they have to be converted into forecasts.

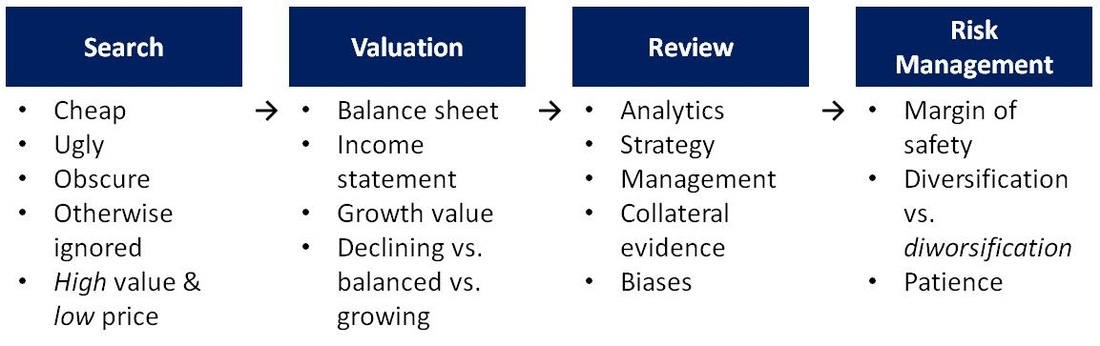

In order to find (screen) and evaluate investments stocks I use the process described below. Finding value investments takes a lot of time and effort. At Richland IH we use Validea to help us screen our possible investment candidates. Once Validea shows me possible candidates I start using the process above. The Value Continuum

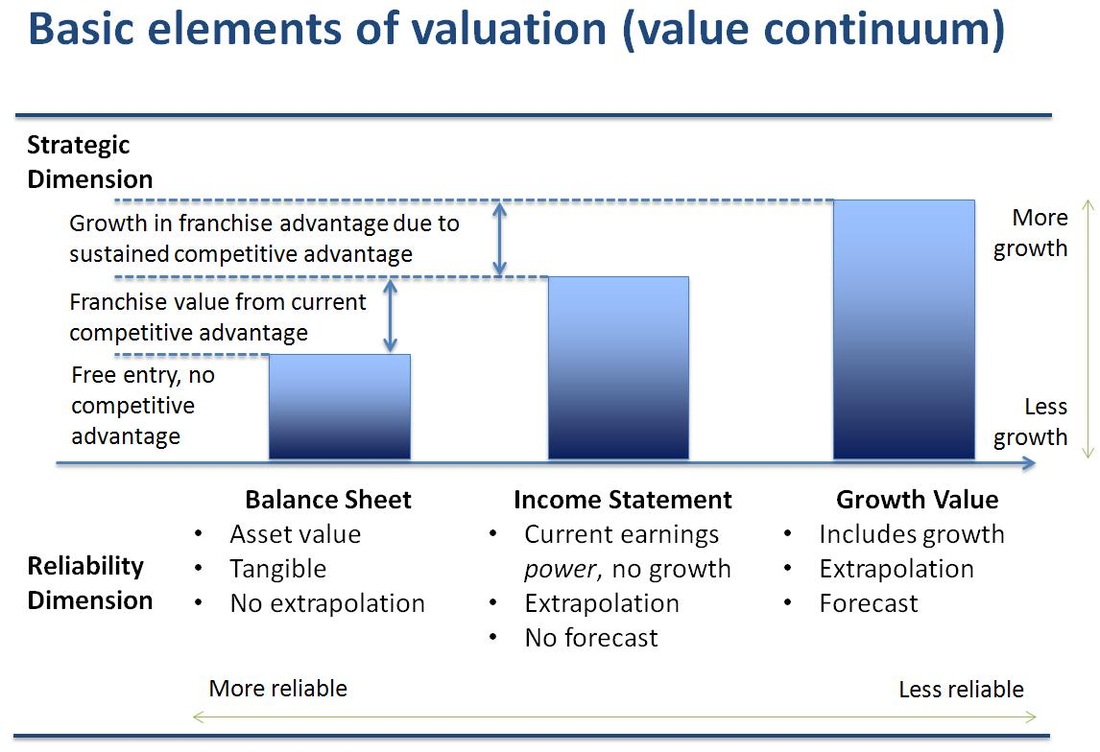

Putting the Balance Sheet (existing assets), Income Statement (earnings power), and growth assets together allows me to define the value continuum (see figure below). The first valuation I posted on this site, i.e. the one done on Bowler Metcalf Ltd, demonstrated this continuum perfectly.

In Bowler's case the asset value was consistently less than the earnings power value which, in turn, was less than the growth value. As explained in the analysis, this is a sign of a firm with a durable competitive advantage, i.e. the kind of firm a value investor loves to invest in all else being equal.

These three intrinsic value calculations will always form the basis of my firm valuations. Once intrinsic value has been determined the true value investor will only make purchases only at prices far enough below intrinsic value to provide a margin of safety that would offer appropriate protection against the variance in the different valuations.

Please Note - DCF (growth value) Equity versus Firm Valuation

When valuing a business (using a Discounted Cash Flow approach) there are two ways which we can approach it. The first is to value the entire business, both assets in place and the growth assets. This uses the Free Cash Flow to Firm, and Weighted Average Cost of Capital, generated by the business in the DCF and this is called the enterprise value. The second method is to value the equity in the business. This uses the Free Cash Flow to Equity, and Cost of Equity, generated by the business in the DCF and is called the equity valuation. These two values are tied to each other and the net difference between the two is the value of any cash & marketable securities and net debt position of the business.

When I perform a growth intrinsic value calculation I do both (equity value and firm value) just to make sure I have not done something wrong. These two figures are never exactly the same, but they are usually close enough not to make a difference and that's good enough for valuation purposes.

I will not delve into more of the detail here. I will spend more time in a follow-up post to provide more detail. I hope this brief overview has provided you with some insights into the financial statements and how they are used to help you understand intrinsic value.

There is so much more to add to this subject, just consider the hundreds (or thousands) of books available on this subject and the importance to the economy and our lives in general. I want to write much more on this matter and I will add ideas and special posts in future on this subject. I will try and pick topics and ideas that are specific to value investors in order to help them make better investment decisions.

Please send me your comments or questions. I look forward to hearing from you.

Be Extraordinary!

Myles Rennie

At Richland IH we are continuously valuing listed common equities in order to identify great value investment opportunities for us and our investment partners. We have a steadily growing capital base and list of investment partners keen to understand and learn how to create sustainable wealth over the long term. At Richland we follow very clear investment identification guidelines as laid out by Benjamin Graham and Warren Buffett (discussed in some of the posts below). Additional to their philosophies I have added my own valuation criteria over time to ensure that we protect the principle of our investment partners to our best ability. Benjamin Graham defined an investment operation as: "one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and an adequate return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative." Therefore, all investments made at Richland follow this thinking. Following Graham and Buffett there are four major criteria that any investment has to comply with: - It should be a simple business to understand within my circle of competence

- It should have good management in place

- It should have a sustainable or durable competitive advantage

- It should have favourable economics

These four main criteria set the stage for the valuation process that I follow. Some of these criteria are qualitative and some quantitative. The first three criteria can be grouped into what I term the Phase I valuation, i.e. is this a company I would like to invest in?. The last criteria falls into Phase II of my valuation, i.e. should I buy based on the economics and current market price?. Note that I will focus here more on the quantitative analysis, and therefore start from point three onward (i.e. it should have a sustainable or durable competitive advantage).

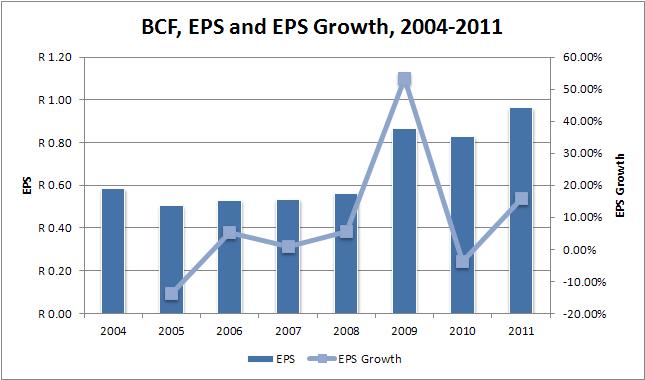

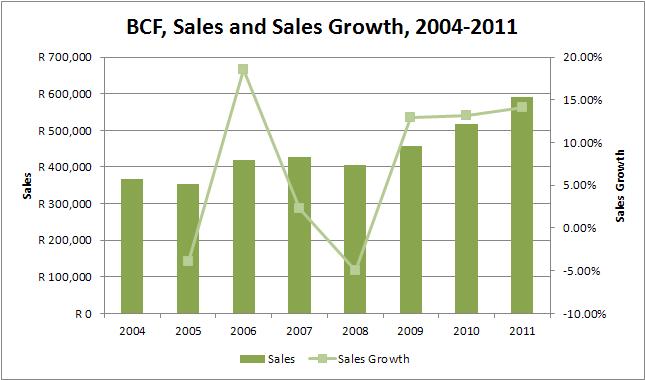

Phase I: is this a company I want to invest in? I will start my valuation of Bowler Metcalf Ltd (ticker symbol: BCF), a company that we follow and invest in at Richland IH, by examining the stability and competitiveness of BCF. The very first criteria I look at it stability in both Earnings per Share and Sales per Share (see figure below).

Stability and Growth of EPS and SPS of the business

The figure shows the EPS and SPS over the last 8 reported full year results. I like companies to have solid, stable earnings and sales that are continually expanding. This allows me to accurately (as far as possible) predict future earnings and sales.

I measure the stability or consistency of the growth of historical earnings per share from year to year, expressed as a percentage in the range 0 to 100 percent. High stability percentage corresponds to high stability and low stability percentage corresponds to low stability. Stability of 100 percent signifies complete stability, meaning that the data is changing by exactly the same percentage each year. The function I developed to calculate the stability percentage has the feature of adjusting for data that could overly distort the result, such as one-off extreme data points, negative data, and data near zero. It also puts more emphasis on recent data.

BCFs EPS stability is 86% which indicates a high level of stability given that we have just come through the biggest world-wide recession of the last 80 years. BCFs sales per share stability is even higher at 93% indicating that even during the recession, the sales activity continued to be stable.

Next we consider the 8 year growth rate of both EPS and SPS. The function I developed to calculate the historical growth rate does not simply calculate either the average or compound growth rate of the 8 years, it considers the annual growth rate year on year. It shows that EPS grew by 9.37% year on year wheres the SPS grew slightly lower at 8.10% per year. Both the EPS and SPS grew at rates higher than the average South African medium-term inflation rate (roughly 6%).

The high stability scores, as well as the growth rates higher than medium-term inflation rates, are the first indicators that BCF has a durable competitive advantage. The figures below show respectively EPS vs. EPS Growth and SPS vs. SPS Growth for BCF.

I particularly look for stocks that have stability percentages of 80 percent or more for both their earnings and their sales. If a company does not satisfy this criterion, I usually just pass it by. After all, if there was little stability in sales and earnings in the past, then it becomes virtually impossible to make confident forecasts for the future.

BCF pass this criteria. Average ROE and ROIC of the business

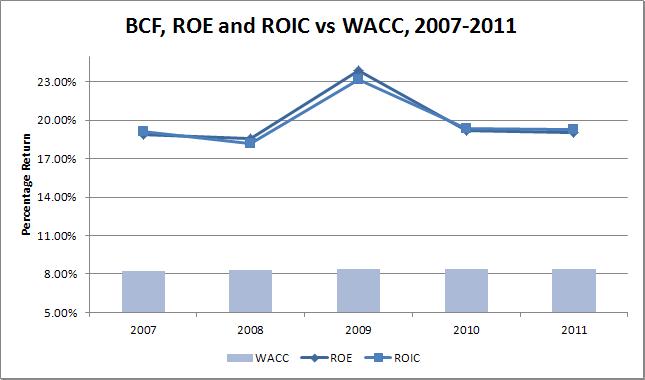

I like companies with above average Return on Equity (ROE) of at least 18% or better, as this is another indicator that the company has a durable competitive advantage. Because some companies can be financed with debt that is many times their equity, they can show a consistently high ROE, yet still be in unattractive price competitive businesses. To screen out these companies I consider a companies Return on Invested Capital (ROIC), which must be higher than 15% and it must be higher than the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) of the company. | | If a company that can maintain its ROIC consistently above its WACC is creating value for its shareholders. A company that has a ROIC lower than its WACC, irrespective of the rate of growth of the company, is destroying value. In fact, when ROIC is smaller than WACC, then the faster the company grows the faster it is destroying value! | Calculating the WACC of a business could be a complex task. There are many different ways of calculating the Cost of Equity and the Cost of Debt of a business. The calculations for BCFs WACC is not displayed here, but if required please email me (see the contact me form) and I will gladly supply the calculations (and the thinking). Suffice it to say, that with a BETA of between -0.01 and 0.01 one can assume that BCFs WACC should be very close to the South African Risk Free Rate (which I assume, most of the time, to be 8.5%).

BCFs average ROE over the last five years was 19.9% and its average ROIC over the same period was 19.83%. The average ROE is higher than the required 18% and the average ROIC is higher than the required 15%. Furthermore, the ROIC is much higher than the average WACC of 8.36%. Therefore, management is creating value for shareholders at a good pace.

The consistently high ROE and ROIC rates is the second indicator that BCF has a durable competitive advantage.

BCF pass this criteria. Corporate Stability of the business

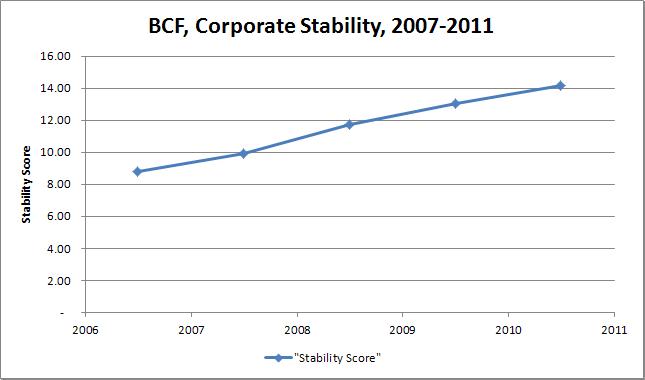

I like companies that demonstrate a high level of corporate stability over the long term. The functions I have developed to measure corporate stability consider a number of different financial ratio's of a firm to determine a stability score. A high corporate stability score is required before considering any investment in the company.

| | A score above 8.15 indicates little chance of the business failing based on current management principles. The average stability score for BCF over the last five years has been 11.54 which is much higher than the required 8.15 for a very stable company. | This is the kind of company I like to invest in, because it has a good chance of still doing what it is doing, and being in business, 10 years from now. BCF is the kind of business I can invest in and forget about, come back in ten years, and it is still going strong.

The consistently stability score is the third indicator that BCF has a durable competitive advantage.

BCF pass this criteria.

Capital expenditure of the business

I like companies that do not have major capital expenditures, i.e. I look for companies that do not need to spend a lot of money on major upgrades of plant and equipment or on research and development to stay competitive.

BCFs free cash flow per share of 57, 90, 105, 69 cents over the past four years are all positive, indicating that the company is generating more cash that it is consuming. This is a favorable sign, and so the company passes this criterion.

BCF pass this criteria.

Debt position of the business

I like businesses that are conservatively financed. Nonetheless, I am willing to invest in firm with solid bond ratings. In South Africa it is not always easy to obtain a bond rating for a firm, and therefore I have developed functions that calculate a synthetic bond rating based on the fundamentals of the business. BCFs synthetic bond rating is calculated as "AAA" based on both its corporate stability rating and the fact that its interest cover ratio is very, very high. In fact, BCF shows R16 500 000 of debt on its balance sheet (31 June 2011), and earnings of R 77 000 000 (31 June 2011). Therefore, it is able to take some of its R77m profit and pay off its debts in one go if it has to, which is considered exceptional.

BCF pass this criteria. Use of Retained Earnings by the business

This is one of Buffett's main screening criteria, and I love it was well. Buffett likes to see if management has spent retained earnings in a way that benefits shareholders. To determine this, Buffett takes the total amount of retained earnings over the previous eight years of R 4.14 per share and compares it to the gain in EPS over the same period of 37.9 cents. BCFs management has proven it can earn shareholders a 9.16% return on the earnings they kept.

This return is average, and slightly higher than the South African Risk Free Rate. Essentially, management is doing a OK job putting the retained earnings to work, but by no means a fantastic job.

BCF has a No Fail on this criteria, but it is not a pass.

This concludes the quantitative elements of the Phase I valuation. Next the valuation moves to Phase II. Phase II: should I buy based on the economics?

If and when I get positive responses to all the above criteria, I then proceed with a value vs. price analysis. The value analysis will determine whether or not the stock should be bought. The following is how I evaluate BCF quantitatively.

I start by understanding the intrinsic value of the business from the perspective of the Balance Sheet, Income Statement, and finally the Free Cash Flow. Intrinsic Value of the business - Balance Sheet

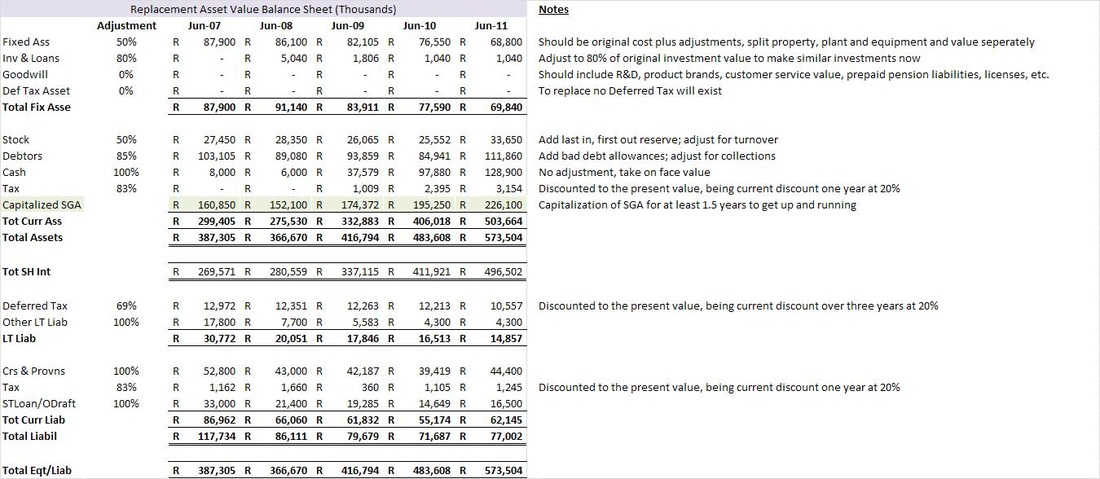

The first step in a Graham valuation is to calculate the asset value of the firm. Many (traditional) value investors see this as the only step to follow. I like to calculate the Asset Replacement Value for the firm. In BCFs case I started with the actual Balance Sheet (BS) for the last five years. Each of the rows in the BS is adjusted by the factor to produce the replacement BS.

The Adjustment column shows the percentage adjustment made for each line item from the original published BS. The Notes column at the end shows why an adjustment was made for an item. The Tot SH Int row shows the Adjusted Book Value for BCF for the years displayed. On a per share basis the Adjusted Book Value per Share is 308, 321, 403, 513, 617 (all values in cents) with each value corresponding to the year 2007 to 2011. This is my intrinsic Balance Sheet values for BCF. Intrinsic Value of the business - Income Statement

Understanding the value of the business from the Income Statements (IS) perspective helps me to understand how hard BCFs management is sweating their assets, i.e. are they managing to grind their assets harder in order to make good returns with the assets they own. I start by looking at BCFs Return on Assets (ROA). BCFs annual ROA over the last five years was 12.58%, 13.78%, 18.65%, 15.68%, 15.83% with an average of 15.30%. This shows that BCF has been able to work their assets hard.

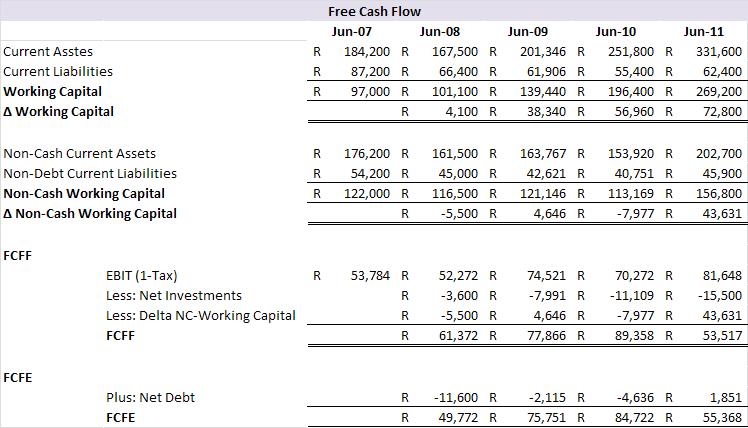

The free cash flow calculations indicate positive free cash flow to both Firm and Equity holders for the last five years. To understand, from the perspective of a value investor, the Earnings Power Value (EPV) of the business, I start by taking the Free Cash Flow to Equity Holders (FCFE) and capitalizing it by the cost of equity (if I worked with the Free Cash Flow to the Firm I would have used to WACC to capitalize the free cash flow).

Calculating the BCFs EPV yields 673, 1071, 1248, 814 cents per share with each value corresponding to the year 2008 to 2011. This is my intrinsic Income Statement values for BCF.

Intrinsic Growth Value of the business - Discounted Cash Flow (DCF)

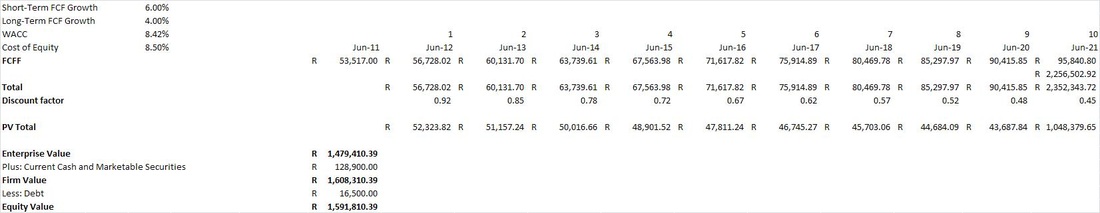

Most value investors don't even attempt to perform a DCF valuation. I do it to see what the possible, yet conservative, upside value of the business could be. Therefore, a DCF of BCF gives me the top or maximum intrinsic value per share. The figure below shows the DCF performed for BCF. I assumed higher growth for the next ten years (very conservative at 6% per year) with a long-term growth rate of 4%. I used the forward-looking WACC to calculate the discount rates.

At the bottom of the figure the Enterprise, Firm and Equity value of BCF is displayed. Based on the Equity value calculated the intrinsic value per share is calculated at 1978 cents. When I perform the DCF but starting from the FCFE perspective, I obtain an intrinsic value of 1866 cents per share. These numbers should be the same, and I can accept in this case that they are sufficiently close together to show that the calculations are sound. Intrinsic Value - putting it all together

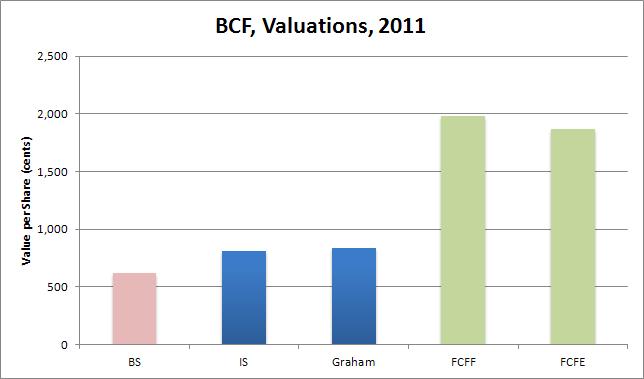

From the exercise above we have obtained three different values for BCF. I usually also do a Graham Valuation as described in Chapter 39 of his 1962 Security Analysis. The value (which is based on earnings) is calculated for BCF using Graham's approach and is shown in as the middle bar in the graph below. Note that BS shows the Replacement Asset intrinsic value. IS shows the Earnings Power Value. FCFF and FCFE respectively show the DCF value form the perspective of mentioned. What is important to note in this graph is that BS is less than IS and BS is also less than Graham. This is the fourth and final indicator that the business enjoys a durable competitive advantage. Furthermore, IS and Graham are both less that the valuation considering growth, i.e. FCFF and FCFE. The bars in this chart show the classic style of a company with a durable competitive advantage: they sweat their assets very hard and therefore have a consistent gap between asset values and earnings values. This graph only shows the valuations for 2011, but in my analysis this gap is positive for the last five years.

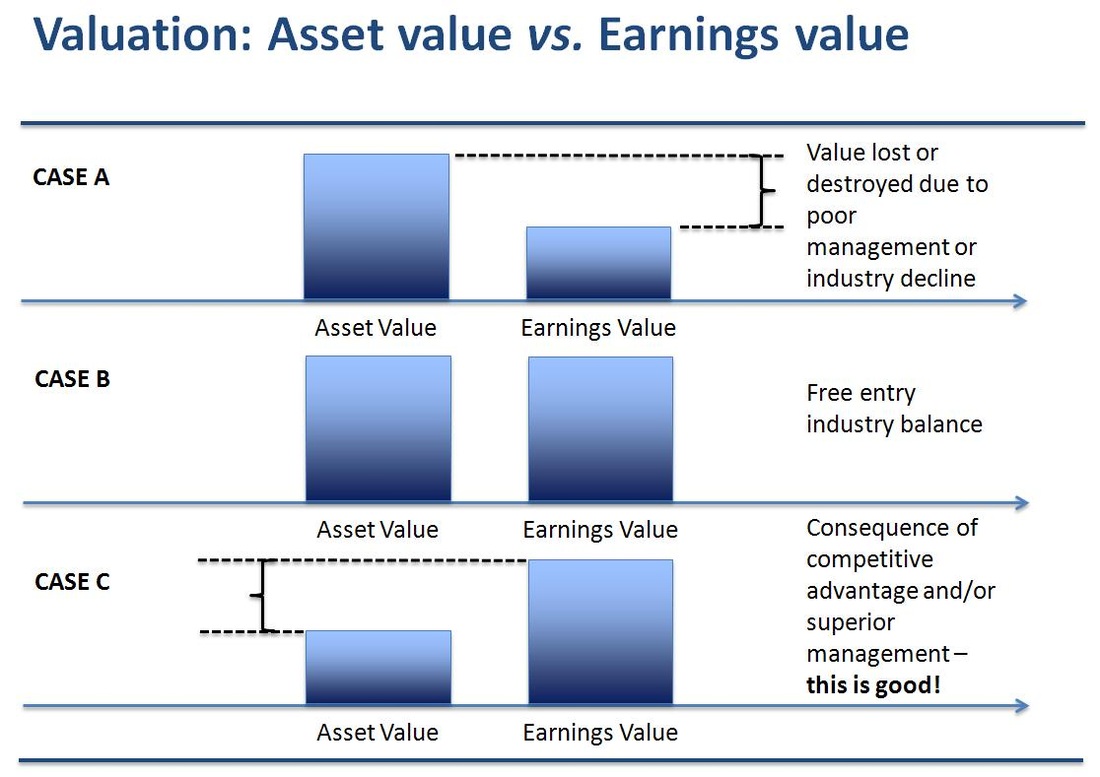

Prof. Bruce Greenwald, in his book Value Investing: From Graham to Buffett and Beyond, defines the details of the relationship between asset value (BS) and earnings power value (IS and Graham) and how this, if the relationship is consistent, is an indication that the firm has durable competitive advantage (see the figure below for simple explanation). Based on the analysis above a fair price to pay for BCF (at the end of June 2011) would be somewhere near R 8.50 per share. Paying more than that would imply paying for potential growth, not something a value investor likes to do. To be honest, a value investor likes to buy assets at a discount (and so do I). Therefore, a value investors buy price would be 75% of the fair value: R 6.38 = R 8.50 x 75%.

In order to make the final investment decision I have to consider what my potential return on investment (ROI) could be if I bought at either R 6.38 and R 8.50. In order to do that I have to determine what the possible future share price could be in 10 years time, using the information I have already gathered and analysed on BCF.

Based on valuations what is the expected return in 10 years?

The final step in the valuation is to determine what the expected share price value could be in 10 years time given the current book value, earnings per share (EPS), payout ratio, P/E ratio, and EPS growth rate. I perform two calculations to determine the possible future share price. The first method starts from the perspective of ROE and the second starts from EPS.

The ROE method starts by determining the average payout ratio. I calculated it as 24.04%. I calculated the average ROE for BCF as 19.90%. This provides the average ROE after payout at 15.11%. Using this as an estimated equity growth rate (based on the relationship to estimate fundamental growth rates = Retention Ratio x ROE) I calculate the equity per share in 10 years to be R 20.69. This yields, given the average ROE, EPS in 10 years of R 4.12. I then calculate the expected price per share in 10 years (using the average P/E over the last 8 years) as R 39.95. Note that to calculate the final share price I add the cumulative expected dividend per share for the 10 future years. Finally, I calculate the expected compound growth rate between R 8.50 (current share price) and R 39.95 (possible future share price in 10 years) as 16.74%. If, however, I calculate the compound annual growth rate between R 6.38 (the margin-of-safety buy price) and R 39.95 it yields 20.13% return.

The second method starts by estimating the future EPS in 10 years using the EPS growth rate calculated earlier. This yields EPS in 10 years of R 2.36. Using this estimated EPS I calculate the possible future share price as R 24.55 (using a similar method as described in the paragraph above). Finally, I calculate the expected compound growth rate between R 8.50 (current share price) and R 24.55 (possible future share price in 10 years) as 11.19%. If, however, I calculate the compound annual growth rate between R 6.38 (the margin-of-safety buy price) and R 24.55 it yields 14.43% return. Interpreting the resultsThe final step is to review the results. Based on my calculations I can show the following: - buying BCF at R 8.50 could yield a possible return of between 16.74% and 11.19%, with an average of 13.96%. This presents a good investment opportunity.

- buying BCF at R 6.39 could yield a possible return of between 20.13% and 14.43%, with an average of 17.28%. This presents a great investment opportunity.

BCF is a good buy. It passes all the key criteria and even buying at fair value still presents good investment opportunities. However, buying at the margin of safety price provides true value investor returns. Buffett managed to secure 20%-plus compounded annual returns over more than 40 years by buying at the right price and sticking to his strategy. My recommendation therefore is to buy BCF at prices from R 8.50 and below.

I would suggest buying BCF at prices from R 8.50 and below. I would not pay more than R 8.50 per share for BCF due to the declining expected future return.

I hope you have enjoyed this first valuation exercise. This is the first of many and will try and post one every couple of weeks. I plan to adjust, or add to, some of my investment criteria with following posts. I also plan to elaborate on the thinking behind the investment criteria with follow-up posts. This will allow people following these posts to gain an understanding of my thinking.

Please feel free to contact me in case you have any additional questions or suggestions regarding the valuation.

Be extraordinary!

Myles Rennie

P.S. The above analysis should not be considered investment advice. I will not be held liable for any investment decisions, or investments, made based on my analysis.

Knowing what a business, an asset, is worth and what determines that value is a prerequisite for intelligent investment - in choosing investments for a portfolio, on deciding the appropriate price to pay for a share of a publicly traded company, and in making choices when running a business. Value investors believe they can make reasonable estimates of value for most businesses. You could ask the question, if you are buying shares why worry so much about the value of the businesses? The answer lies in what Benjamin Graham said: that every corporate security may best be viewed, in the first instance, as an ownership interest in, or claim against, a specific business enterprise. Understanding valuation will further allow the intelligent investor to identify and understand value creation - a necessity for choosing investments that have a greater chance of yielding better that average returns over the long term (i.e. identifying businesses with growth potential - with a sustainable competitive advantage).

It is true that some assets are easier to value than others, and although uncertainty with value estimates is different for different assets, the core principles remain the same.

Happy Investing and Be Extraordinary!

Myles

Benjamin Graham is commonly credited as establishing the discipline of security analysis and being the father of Value Investing. He promoted investment as a rational activity, an approach which requires the investor to return to the financial statements in order to avoid huge mistakes and misjudgments. In his seminal book Security Analysis, published in 1935, Benjamin Graham started sharing his approach and ideas with both professionals and casual investors. He drew a line in the sand between investment and speculation. He defined an investment operation as one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and a satisfactory return. Any operations not meeting these requirements are speculative. With the publication of Security Analysis the concept of the Value Investor was born, i.e. someone who seeks to purchase a stock at a bargain price – buying a RAND for fifty cents or put differently buy cheap (or rather good value) and sell dear. One can infer from this that there are times during the market cycle when value investors will have fewer opportunities and times when they will have more opportunities in the market. In short, value investors have more buying opportunities in bear markets than bull markets.

Toward the latter stages of bull markets value investors find it very hard to find cheap stocks, whereas there are many businesses falling into this classification toward the end of a bear market. Another interesting phenomenon is that it is almost always toward the end of bull markets that investors (or the markets in general) stop paying attention to fundamentals like book value, cash flow, interest, and various other fundamental ratios to value common stock. These are the greedy times as Buffett calls them (and when he is fearful of the markets). Two examples in recent memory springs to mind: the Dot-Com bubble of 2000 and the American Sub-Prime Housing bubble of 2007. In both cases greed and herding resulted in fundamentals being discarded for the more attractive, and at the time more lucrative, new economy thinking. During both these periods it looked as if value investors were an endangered species. This is because proponents of the New Economy hypothesis always argue that some of the fundamental truths of economic reality had been repealed and that value investors’ days are numbered and are being left behind. Value investors’ opinion will be that the market levels are in the tulip mania (see post below) territory, whereas new economy proponents will argue that the good times are here to stay and that markets will keep on rising. Value investors are very patient and therefore not deterred from their approach. They know that the most important thing when employing a decipline is consistent implementation. Therefore, they quietly await the ever looming bear market that will present the perfect time for them to find great buys (i.e. good valuations) at low prices.

Graham’s original ideas still remain relevant today. Graham’s best known student, or disciple as he likes to refer to himself, is value investor Warren Buffett, whose track record and global fame speaks for itself. Buffett, who had studied different investment theories since the age of 11, says he was struck by the compelling logic of Graham’s approach when he first encountered it. Buffett is by no means the only Graham success story in the world, many other have equally impressive track records, e.g. all the super investors from Graham and Doddsville. Some people refer to Buffett’s approach to value investing as growth-at-a-reasonable-price investing, rather than pure value investing. Buffett's approach is value investing but combined with elements of growth investing, even though Benjamin Graham himself was not a great supporter of valuing and considering potential business growth. In short a growth-at-a-reasonable-price investor buys high quality growth companies when they are experiencing temporary difficulties and have therefore lost favour in the market and thus have an artificially suppressed market price (i.e. buy a RAND for 50 cents).

Since Security Analysis, and later the Intelligent Investor, many other investment approaches have emerged. During the 1950 and 1960 the very popular modern investment theory, based on rigorous mathematical and statistical analysis and on what’s know as the efficient market hypothesis, emerged. Other investment approaches that emerged include growth investment, momentum investment, technical investment, to name but a few main ones. In the last decade or two behavioural finance emerged. Its been built on psychological research that advocates the idea that investors act based on emotions and other factors, e.g. herding behaviour, the tendency or biases to give more significance to the most recent news, good or bad, etc. Behavioural finance challenges the fact that people are unemotional and always act 100% rational, a premise of the efficient market hypothesis. This finding about excessive reaction confirms a long held Value Investing belief that over the long run, the performance of both businesses and their share prices will revert to the mean. At the core of most investment approaches lies the skill, or art, of business valuation, i.e. the technique by which the real or intrinsic value of a business is estimated. Value Investors want to buy stocks whose true value (per share) is much more that the market price (per share) of the stock, because Value Investors believe that over time the market price will reflect the intrinsic value of the business, i.e. it will revert to the mean as mention above.

There are many approaches to valuing businesses. There is general agreement that John Burr Williams’ approach, published as The Theory of Investment Value in 1938, of summing the estimated cash flows a business will produce over its life, and discounting it back to its present value, will yield the value of the business. This is called the discounted cash flow (DCF) approach, present value (PV) approach, or a newer approach called adjusted present value (APV). Then there is the route of multiples, i.e. …. Newer theories, based on option pricing theory, called Real Option Pricing (or Real Options), value businesses like quants value options (for more on Black-Scholes pricing models see Fischer Black and Myron Scholes' 1973 paper The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities). Graham’s approach started with what the business is worth today, rather than to rely only on assumptions about events and conditions far into the future. Therefore, value investors prefer to value a business first by examining the assets of the business, then to look at the earnings power of the business, and if the business shows signs of competitive advantage they value the growth potential of the business via cash flow forecast and DCF analysis.

Graham’s skepticism of cash flow forecast and valuing growth potential is simply because he believed that in most cases the growth is not worth much. In most competitive environments all the value of the growth will be used to buy additional capital required to enable the growth. Therefore, Graham’s approach only values growth that produces returns in excess of the cost of the additional capital, i.e. a type of economic growth which generally only businesses generating excessive profits achieve. One of Warren Buffett’s well publicized criteria to picking winning investments is that the business, underlying the investment, should have a sustainable competitive advantage, this is because he is looking for the growth stocks at value prices. Businesses with a sustainable competitive advantage are in some way protected, by various forms of barriers to entry (or what Buffett calls a business moat), from competitors entering their market and driving down their excess profits. Therefore, value investors interested in the growth value of a business will pay careful attention to the strategic positioning of the business. Again ahead of its time was that this assessment of the strategic position of a business, now commonplace among the most sophisticated investors, was inherent from the start in Graham’s approach. Next we consider the basic tenets of value investing as well as valuation in a little more detail.

Be Extraordinary!

Myles

George Santayana said that those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. The history of stock markets are fascinating and provides valuable lessons to the modern day investor. This post is a very, very brief overview of stock markets, their origins, and the early days.

The first financial instruments traded in the world were debt. The ancient Mesopotamian society created interest-bearing loans. In the Roman Republic, long before the existence of the Roman Empire, there were societates publicanorum, organizations of contractors or leaseholders who performed temple-building and other services for the government. Participants in such organizations had partes (i.e. parts) or shares. Tradable bonds as a commonly used type of security were a more recent innovation, spearheaded by the Italian city-states of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods.

War instigated the development and maturity of bonds as we know it today. Sometimes bonds were issued and sold to voluntary buyers and sometimes they were more like forced loans from the citizenry. Initially regarded with suspicion, it came to be seen as a valuable investment that could be bought and sold. The bond market had begun.

By the late 1500s, British merchants were experimenting with joint-stock companies intended to operate on an ongoing basis. Unofficial stock markets existed across Europe through the 1600s and brokers would meet at coffee houses to trade stocks and bonds. In 1602 the Dutch East India Company (Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC) was formed and Amsterdam became the first official stock exchange. The VOC established the exchange and issued corporate VOC shares. Control of the company was held tightly by its directors, with ordinary shareholders not having much influence on management or even access to the company's accounting statements. However, the returns offered to early shareholders were lucrative, an average dividend of 16 percent per year from 1602 to 1650. Reinvesting the dividend back in shares would have earned an early investor 16 percent compound annually.

By the early 1700s there were fully operational stock exchanges in other parts of the world. Stock exchanges became an important way for companies to raise capital for investment, while also offering both investors and speculators the opportunity to share in company profits and benefit from the fluctuations of stock prices. New techniques and instruments quickly proliferated for securities as well as commodities, including options, repos and margin trading. Sophistication and opportunity quickly grew in the markets.

Since inception stock markets have attracted both investors and speculators. The first author known to have published a book on stock markets and investing was Joseph de la Vegain in 1688. His book Confusion of Confusions explained the workings of stock markets, he warned about the potential excesses, he described stock trading, he highlighted the unpredictability of market shifts, and he explained the importance of patience in investment. Since the early days people were trying to formula strategies to better investing...and speculation.

The first speculative stock market bubble was Tulip Mania during the Dutch Golden Age. It lasted 4 months with its peak in February 1637, when a single tulip bulbs sold for more than 10 times the annual income of a skilled craftsman. Many people lost everything in the mad rush to make money. The British journalist Charles Mackay’s wrote the book Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds in 1841 to describe the bubble and the behaviour of speculators witnessed at the time. The behaviour he describes is still common today. The second big bubble occurred a few decades later. At the center of it were the South Sea Company, set up in 1711 to conduct English trade with South America, and the Mississippi Company, focused on commerce with France's Louisiana colony. Investors (... and speculators) snapped up shares in both, and whatever else was available. In 1720, at the height of the mania, there was even an offering of a company for carrying out an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is. By the end of that same year, share prices were collapsing, as it became clear that expectations of imminent wealth from the Americas were overblown. In London, Parliament even passed the Bubble Act, to stop people issuing shares to unsuspecting investors (... and speculators).

Since those early days different approaches to investment and speculation have been formulated. Many people proposed approaches which, on paper, would yield grand returns. However, the markets were dominated by speculation, insider information, and other practices which could at best be described as unethical and borderline criminal. Then, in the early 20th century, Benjamin Graham changed all that, which I will write about in my next post.

Be Extraordinary!

Myles

What are some great sources of investment opportunity? Source include stock market correction or panic like a bull-to-bear market switch, industry recession, business calamity, war, or structural changes? The perfect buying situation is when a stock market correction or panic is coupled with an industry recession or an individual business calamity or structural changes or war.

Recessions signal the start of great buying opportunities, for the value investor with spare cash available. Recovery time from a recession is generally anything between one to four years and during this time there are excellent buying opportunities. During recessions the manic-depressive Mr. Market goes into panic mode and out of fear offers to sell great companies often at single digit PEs. The true value investor understands that during a recession period everyone gets hurt, but the strong survive while the weak are removed from the economic landscape. Sticking to intrinsic value calculations and focusing on business fundamentals, while ignoring manic price fluctuations, allows the value investor to pick up fantastic businesses at bargain sale prices.

Recessions are so important to the value investor we will discuss it further. George Soros, the famous macro investor, observed business boom-bust cycle markets so often during his career he formulated a graphical model of it and constructed his own market theory he called reflexivity. In his market theory he does not specify the cause of such boom-bust cycles, but he speculates that they always have a political element. Government economic intervention as the cause of business cycles has been extensively written about by various authors, including those from the Austrian School of economics. They write that an extra market force (in the case the central bank of a country) can initiate an artificial, or unsustainable, economic boom. They further write that a money-induced boom contains the seeds of its own destruction, i.e. the market upturn, must by the logic of market forces set in motion, be followed by a downturn.

When markets, or the economy as a whole, are not performing optimally politicians can interpret this situation as a threat to their elected positions. If they do, they will often take corrective action to rectify the situation before it becomes a political issue during election time. One of the popular methods of stimulating economic activity is to increase the money supply. This expansion of the money supply leads to lower interest rates. In turn lower interest rates generally lead to an overconsumption in the market as well as lower discount rates (i.e. lower cost of debt thus lower weighted cost of capital). These lower discount rates in turn lead to increased business valuation calculations, or valuation inflation, and increased malinvestment to the valuation inflation.

Over-consumption and lower cost of debt leads to increased revenues, allows businesses to expand, and leads to greater profits. This process can very easily lead to a speculative bubble, i.e. from price increases due to valuation increases, to increased investor enthusiasm, to increased demand, and hence further price increases. When a bubble starts forming, substitutes for business fundamentals start to justify the politically motivated economic boom. Therefore, as fundamental data no longer justifies the boom, market participants replace fundamental analysis with fundamental substitute analysis that will support the boom. These substitutes are always consistent with the perceived new economic conditions driving the boom (e.g. stocks are values at multiples of revenue, not earnings, and growth is funded by selling stock, not executing sound business plans). This leads to a situation where a substantial gap between market behaviour, or speculation, and fundamentals forms and widens.

This ever widening gap however cannot continue indefinite and at some point the market has to correct, it has to abandon the substitutes and re-establish fundamentals. This does not happen however before the last marginal investors in the market buy in. As the old saying goes: what the wise man does in the beginning, the fool does in the end. This final marginal buying further fuels the gap and is the boom’s final push. At this point the politicians have to cool down the market bubble in order to avoid a market crash. Interest rates are raised to reduce consumption and increase discount rates, which causes valuations to decline and malinvestment to halt.

Now the actual fundamentals start to decline as a result of lack of buying and together with rising interest rates the fundamental substitute’s starts to deteriorate. This deterioration starts the investment liquidation cycle and marginal short selling. This market behaviour feeds off itself resulting in mass selling. This triggers investors to take a so called flight to quality that involves liquidating perceived risky investments in favour of government securities or precious metals to preserve the balance of their portfolios. This process typically continues until the true fundamentals decline below pre-bubble levels. As Warren Buffett says: a pin lies and wait for every bubble, and when the two eventually meet, a new wave of investors learn some very old lessons.

At this point malinvestments are liquidated and recovery of the market can begin. Fundamentals and market conditions reconcile again and economic growth can again begin. There is however the chance of recession or depression, based on the severity of the crash. Therefore, often this phase is met with a new wave of government intervention in order to shorten the duration of the correction cycle and fuel economic growth.

The second of our ideal buying opportunities is linked to business calamity. Sometimes great companies make mistakes which cause them to lose money. This creates concern in the market and their share price reflects this by declining sharply. This in turn represents a great contrarian buying opportunity. The value investor has to determine whether this is a passing calamity or irreversible damage. A company with an identifiable competitive advantage almost always has the financial durability to survive calamity. Deciding whether the calamity is correctable is important. Even more important is whether the calamity affect’s the competitive advantage of the company, in which case the investor should not consider investing. Often just one division of a company suffers a calamity, but affects the entire company. If the investor believes that management can fix the calamity or that the other divisions, with the competitive advantage, can save the company then the investor should consider investing if the price is right.

The final opportunities arise with structural changes and world events like war. Structural changes in a company, like mergers, restructuring, and reorganizations, can often affect earnings negatively and thus negatively affect the share price thereby creating buying opportunities. War, or the threat thereof, will send stock prices tumbling. The uncertainty and great potential for disaster will send fear through the entire market triggering a mass sell-off and a hoarding of cash and safe commodities like gold. This in turn disrupts the entire economy and creates great buying opportunities for the value investor who can determine which companies will recover from the ones that won’t.

Be extraordinary!

Myles Rennie

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed